Many Australians are cooking in a far more isolated environment than we’re used to. That sometimes means being a bit more creative with whatever ingredients we can rustle up.

But when you’re next digging around the back of your cupboard for that old can of kidney beans, spare a thought for the early Antarctic expeditioners, who spent entire winters on the icy continent with very limited cooking ingredients.

And thanks to the diary of the expedition cook, we can get an insight into the dining habits of Australia’s first expeditioners.

The ends of the Earth

In February 1954, a ten-man crew led by Officer-in-Charge Bob Dovers arrived at the outreaches of MacRobertson Land in the Australian Antarctic Territory.

They were there to establish the first Australian base on the continent – Mawson Station, now the longest continuously operating base south of the Antarctic Circle.

The expeditioners' first task was to build the hut that would be their quarters, kitchen, and mess for the next twelve months.

It was hard work, but luckily the fledgling base had a dedicated cook to feed the hungry explorers – Jeff Gleadell, a 42-year-old from Kurri Kurri in New South Wales.

It was Gleadell's second trip to the Antarctic, having worked as a mess boy on Sir Hubert Wilkins 1929 expedition. He told the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate that it would be 'great going to the Antarctic again. If you’ve seen it once, you’ll want to see it again'.

Making do with what’s available

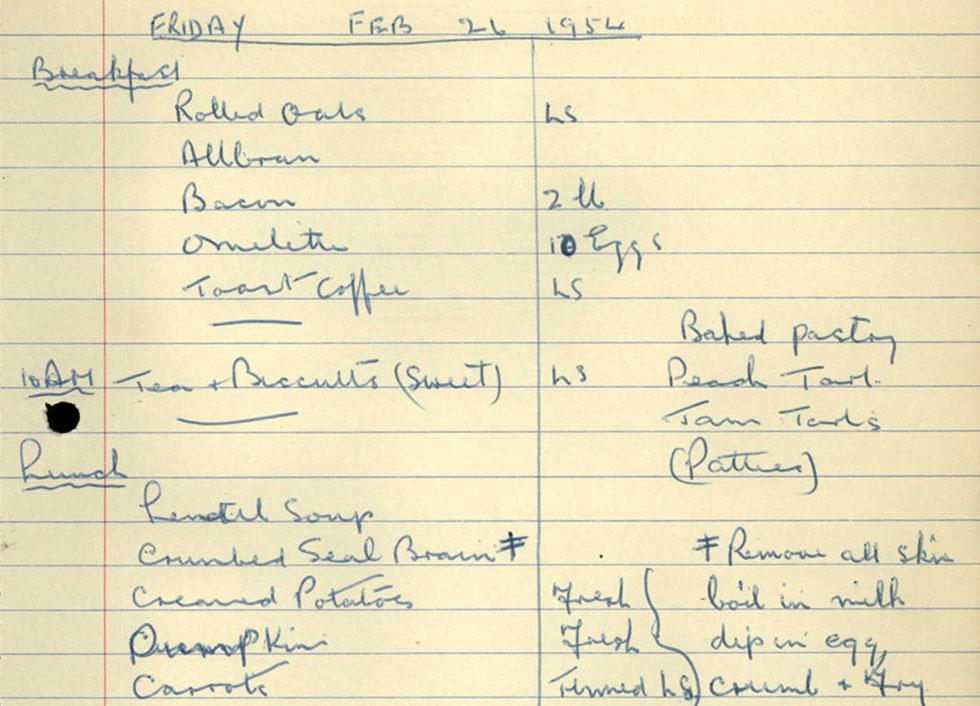

Gleadell’s Antarctic diary records his daily menus for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

It was a cooking challenge that would scare off most MasterChef contestants. Although his kitchen was kitted out with the latest appliances, Gleadell had to mostly cook with frozen, tinned and cured foods brought from Australia.

To supplement these supplies, he made do with whatever ingredients he could find locally. There were no restrictions on shooting or eating Antarctic wildlife in 1954, so local animals sometimes found themselves in the cooking pot.

Weddell seals were shot and butchered for the men and dogs. Seal steak apparently had a gamy, fishy taste and a texture similar to veal. Seal brain cakes were a particular favourite of the crew, while seal liver with bacon and onion gravy was also popular.

Large seabirds called skuas also graced the menu from time to time. They were braised or stewed with vegetables and reportedly tasted a bit like duck.

Gleadell also whipped up plenty of dishes more appealing to the non-Antarctic explorers among us. Before leaving Australia, he told the Australian Women’s Weekly that he planned to make ‘gallons of ice-cream.’ This involved leaving the mixture outside the kitchen door to freeze before serving it with tinned fruit.

Beyond the kitchen

Gleadell wrote about more than just each day’s menu, and his diary gives us a personal, human understanding of day-to-day life in the Antarctic winter.

The cook records aurora activity and the changing weather conditions, including rapidly shortening days and blizzards as winter arrives.

He also sometimes records the moods of his crewmates and the behaviours of the huskies. He’s particularly pleased when one of the huskies breaks free of its restraints and comes to visit him during the day.

Another highlight comes in mid-March 1954, when four emperor penguins came to inspect the new hut being built. (Fortunately for them, penguin does not appear on the next day’s menu.)

The final menu in Jeff Gleadell's diary is Christmas Dinner: a traditional affair of roast pork and apple sauce, Christmas pudding with brandy sauce, and plenty of wine, spirits and liqueur. There are some things a seal steak just can’t replace!

Read the Antarctic cook's diary in RecordSearch, our collection database.