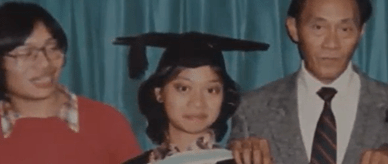

Lam Tac Tam arrived in Darwin as a refugee on a 17-metre fishing vessel in 1976 after fleeing Communist Vietnam. Lam found a job within a week, and negotiated the challenges of a different culture, food and language.

Lam and his Timorese-born wife still reside in Darwin, although he regularly returns to his country of birth for his business promoting tourism to Vietnam.