The corset: has any other fashion item had such a complicated legacy? In its long and fascinating history, it has undergone many changes and controversies. National Archives of Australia contains one part of its story – when two titans of Australian corsetry faced off in a battle for patent supremacy.

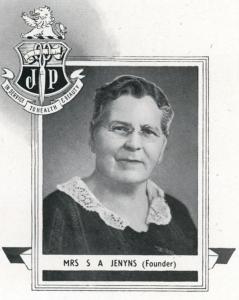

Sarah Ann Jenyns

Born in 1865, Sarah Ann Jenyns trained as a nurse while raising her children with her husband, surgical instrument maker and preacher Ebenezer Randolph Jenyns.

In 1886, Sarah and her family relocated from the New South Wales coalfields, where Ebenezer had been preaching, to Brisbane. It was around this time that concerns were being raised about the effects of corsets on women's health.

Sarah would have worn the short, steel-boned, hour-glass shaped corsets that were common during the period. Doctors were beginning to identify health issues associated with the use of these corsets: damage to the organs, respiratory complications, birth defects and rib deformity. Although there is ongoing contention among fashion historians about the validity of these claims, Sarah herself had no doubts. Something had to change.

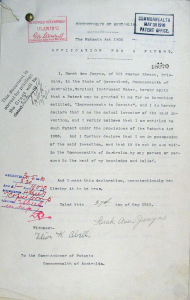

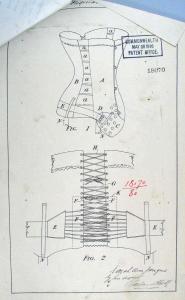

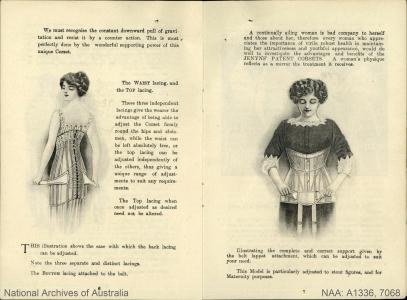

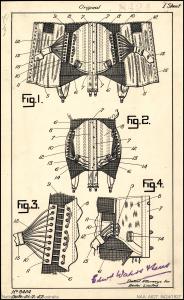

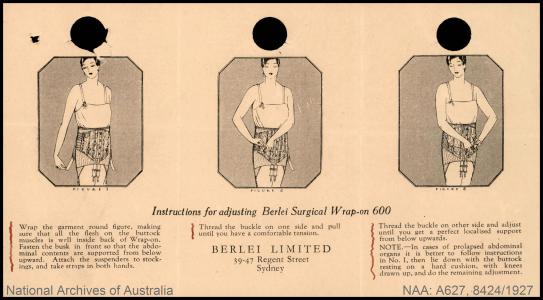

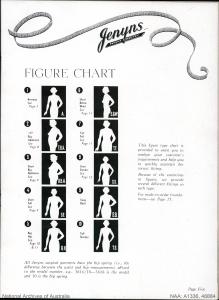

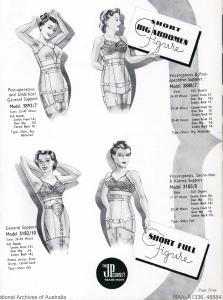

Using her nursing background, Sarah created a series of corsets and surgical belts that were designed to reduce back pain and assist in post-surgical recovery. She replaced the traditional steel or whale corset boning with a new structural mesh called 'Vertabrella'. This new material allowed the garment to move with women's bodies while still providing support. While most corsets were only available in a single shape, her product was suitable for 12 different figure types.

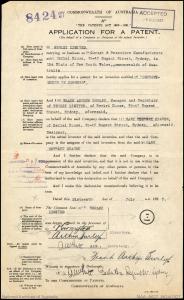

Sarah and her husband started their business selling Sarah's designs in 1907, and by 1909 Jenyns Patent Corsets Pty Ltd was so successful that they had to move to larger premises.